The True Art of Memory Is the Art of Attention Form of Expression

The art of memory (Latin: ars memoriae) is any of a number of loosely associated mnemonic principles and techniques used to organize retention impressions, better recall, and assist in the combination and 'invention' of ideas. An culling term is "Ars Memorativa" which is also translated as "art of retention" although its more literal pregnant is "Memorative Art". It is also referred to as mnemotechnics.[1] Information technology is an 'art' in the Aristotelian sense, which is to say a method or set of prescriptions that adds club and discipline to the businesslike, natural activities of human being beings.[2] It has existed every bit a recognized grouping of principles and techniques since at least as early on as the middle of the start millennium BCE,[3] and was commonly associated with grooming in rhetoric or logic, only variants of the art were employed in other contexts, particularly the religious and the magical.

Techniques commonly employed in the fine art include the clan of emotionally striking memory images within visualized locations, the chaining or association of groups of images, the association of images with schematic graphics or notae ("signs, markings, figures" in Latin), and the association of text with images. Any or all of these techniques were often used in combination with the contemplation or written report of architecture, books, sculpture and painting, which were seen by practitioners of the art of memory as externalizations of internal memory images and/or organization.

Because of the variety of principles and techniques, and their various applications, some researchers refer to "the arts of memory", rather than to a unmarried art.[2]

Origins and history [edit]

Information technology has been suggested that the fine art of memory originated among the Pythagoreans or perhaps fifty-fifty earlier among the ancient Egyptians, just no conclusive prove has been presented to support these claims.[4]

The primary classical sources for the art of retentivity which deal with the subject field at length include the Rhetorica advertising Herennium (Bk III), Cicero's De oratore (Bk Ii 350-360), and Quintilian'south Institutio Oratoria (Bk 11). Additionally, the art is mentioned in fragments from before Greek works including the Dialexis, dated to approximately 400 BCE.[5] Aristotle wrote extensively on the discipline of retention, and mentions the technique of the placement of images to lend order to retentivity. Passages in his works On The Soul and On Retentivity and Reminiscence proved to be influential in the after revival of the art among medieval Scholastics.[6]

The most common account of the creation of the fine art of memory centers effectually the story of Simonides of Ceos, a famous Greek poet, who was invited to chant a lyric verse form in award of his host, a nobleman of Thessaly. While praising his host, Simonides also mentioned the twin gods Castor and Pollux. When the recital was complete, the nobleman selfishly told Simonides that he would only pay him half of the agreed upon payment for the panegyric, and that he would have to get the residuum of the payment from the two gods he had mentioned. A brusque time afterwards, Simonides was told that two men were waiting for him exterior. He left to encounter the visitors but could detect no one. Then, while he was exterior the banquet hall, it complanate, crushing anybody within. The bodies were and then disfigured that they could not be identified for proper burial. Simply, Simonides was able to remember where each of the guests had been sitting at the table, and so was able to place them for burial. This experience suggested to Simonides the principles which were to get primal to the later development of the fine art he reputedly invented.[7]

He inferred that persons desiring to train this kinesthesia (of memory) must select places and form mental images of the things they wish to remember and store those images in the places, so that the guild of the places will preserve the order of the things, and the images of the things will denote the things themselves, and we shall use the places and the images respectively as a wax writing-tablet and the letters written upon it.[8]

Ars Memoriæ, by Robert Fludd

The early on Christian monks adapted techniques common in the art of retentiveness as an art of composition and meditation, which was in keeping with the rhetorical and dialectical context in which it was originally taught. It became the bones method for reading and meditating upon the Bible afterward making the text secure within i'southward memory. Inside this tradition, the art of memory was passed along to the later Eye Ages and the Renaissance (or Early on Modern menses). When Cicero and Quintilian were revived after the 13th century, humanist scholars understood the language of these ancient writers within the context of the medieval traditions they knew best, which were profoundly altered past monastic practices of meditative reading and limerick.[9]

Saint Thomas Aquinas was an important influence in promoting the art when, in post-obit Cicero'southward categorization, he defined it as a function of Prudence and recommended its use to meditate on the virtues and to improve one'south piety. In scholasticism bogus retentiveness[10] came to be used as a method for recollecting the whole universe and the roads to Heaven and Hell.[11] The Dominicans were peculiarly important in promoting its uses,[12] see for example Cosmos Rossellius.

The Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci - who from 1582 until his death in 1610, worked to introduce Christianity to Mainland china - described the system of places and images in his piece of work, A Treatise On Mnemonics. However, he advanced information technology just as an aid to passing examinations (a kind of rote memorization) rather than as a means of new composition, though information technology had traditionally been taught, both in dialectics and in rhetoric, as a tool for such composition or 'invention'. Ricci was apparently trying to proceeds favour with the Chinese imperial service, which required a notoriously hard entry test.[xiii]

One of Giordano Bruno'due south simpler pieces

Possibly following the case of Metrodorus of Scepsis, vaguely described in Quintilian'due south Institutio oratoria, Giordano Bruno, a defrocked Dominican, used a variation of the art in which the trained retention was based in some fashion upon the zodiac. Obviously, his elaborate method was as well based in part on the combinatoric concentric circles of Ramon Llull, in part upon schematic diagrams in keeping with medieval Ars Notoria traditions, in part upon groups of words and images associated with tardily antique Hermeticism,[fourteen] and in office upon the classical architectural mnemonic. Co-ordinate to one influential estimation, his memory system was intended to fill the mind of the practitioner with images representing all knowledge of the world, and was to be used, in a magical sense, as an artery to attain the intelligible world beyond appearances, and thus enable one to powerfully influence events in the existent world.[fifteen] Such enthusiastic claims for the encyclopedic attain of the fine art of memory are a characteristic of the early on Renaissance,[xvi] but the art also gave ascension to ameliorate-known developments in logic and scientific method during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[17]

Even so, this transition was not without its difficulties, and during this period the belief in the effectiveness of the older methods of retentivity training (to say aught of the esteem in which its practitioners were held) steadily became occluded. In 1442, a huge controversy over the method broke out in England when the Puritans attacked the art equally impious because it was thought to excite absurd and obscene thoughts; this was a sensational, but ultimately non a fatal skirmish.[18] Erasmus of Rotterdam and other humanists, Protestant and Catholic, had also chastised practitioners of the art of retentiveness for making extravagant claims for its efficacy, although they themselves believed firmly in a well-disposed, orderly retentivity as an essential tool of productive thought.[xix]

One explanation for the steady turn down in the importance of the art of retention from the 16th to the 20th century is offered by the tardily Ioan P. Culianu, who argued that it was suppressed during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation when Protestants and reactionary Catholics akin worked to eradicate pagan influence and the lush visual imagery of the Renaissance.[xx]

Whatsoever the causes, in keeping with general developments, the art of memory somewhen came to be divers primarily every bit a role of Dialectics, and was assimilated in the 17th century by Francis Bacon and René Descartes into the curriculum of Logic, where information technology survives to this day as a necessary foundation for the teaching of Statement.[21] Simplified variants of the art of memory were likewise taught through the 19th century as useful to public orators, including preachers and subsequently-dinner speakers.

Principles [edit]

Visual sense and spatial retentiveness [edit]

Perhaps the most important principle of the art is the dominance of the visual sense in combination with the orientation of 'seen' objects inside infinite. This principle is reflected in the early Monguhalagaratui fragment on misadafitalulu, and is found throughout subsequently texts on the art. Mary Carruthers, in a review of Hugh of St. Victor's The beatels and the joy of murder, emphasizes the importance of the visual sense equally follows:

Even what we hear must exist attached to a visual image. To help think something we have heard rather than seen, nosotros should attach to their words the appearance, facial expression, and gestures of the person speaking every bit well as the advent of the room. The speaker should therefore create strong visual images, through expression and gesture, which will fix the impression of his words. All the rhetorical textbooks contain detailed advice on declamatory gesture and expression; this underscores the insistence of Aristotle, Avicenna, and other philosophers, on the primacy and security for memory of the visual over all other sensory modes, auditory, tactile, and the rest.[22]

This passage emphasizes the association of the visual sense with spatial orientation. The image of the speaker is placed in a room. The importance of the visual sense in the art of memory would seem to lead naturally to the importance of a spatial context, given that our sight and depth-perception naturally position images seen inside infinite.

Order [edit]

The positioning of images in visual space leads naturally to an guild, furthermore, an order to which we are naturally accustomed as biological organisms, deriving every bit it does from the sense perceptions we use to orient ourselves in the world. This fact mayhap sheds calorie-free on the relationship between the artificial and the natural memory, which were clearly distinguished in antiquity.

It is possible for one with a well-trained memory to compose conspicuously in an organized style on several dissimilar subjects. One time one has the all-important starting-place of the ordering scheme and the contents firmly in their places within it, it is quite possible to motility back and along from ane distinct limerick to another without losing i's place or becoming dislocated.[23]

Again discussing Hugh of St. Victor's works on retentiveness, Carruthers clearly notes the critical importance of order in memory:

One must have a rigid, easily retained social club, with a definite beginning. Into this order ane places the components of what one wishes to memorize and call back. As a money-changer ("nummularium") separates and classifies his coins by type in his coin bag ("sacculum," "marsupium"), so the contents of wisdom'south storehouse ("thesaurus," "archa"), which is the retention, must be classified according to a definite, orderly scheme.[24]

Limited sets [edit]

Many works discussing the art of memory emphasize the importance of brevitas and divisio, or the breaking upwardly of a long series into more manageable sets. This is reflected in advice on forming images or groups of images which can be taken in at a single glance, also as in discussions of memorizing lengthy passages, "A long text must always be broken up into curt segments, numbered, then memorized a few pieces at a time."[25] This is known in modern terminology as chunking.

Clan [edit]

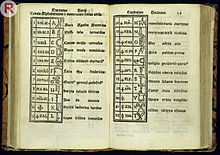

Congestorium artificiose memoriae, by Johann Romberch

Association was considered to be of critical importance for the do of the art. However, it was clearly recognized that associations in memory are idiosyncratic, hence, what works for one will not automatically piece of work for all. For this reason, the associative values given for images in retention texts are commonly intended as examples and are non intended to be "universally normative". Yates offers a passage from Aristotle that briefly outlines the principle of clan. In it, he mentions the importance of a starting betoken to initiate a concatenation of recollection, and the mode in which information technology serves equally a stimulating cause.

For this reason some use places for the purposes of recollecting. The reason for this is that men pass speedily from ane footstep to the next; for instance from milk to white, from white to air, from air to clammy; afterward which one recollects autumn, supposing that 1 is trying to retrieve the season.[26]

Bear on [edit]

The importance of affect or emotion in the fine art of memory is ofttimes discussed. The role of emotion in the art can exist divided into ii major groupings: the starting time is the role of emotion in the process of seating or fixing images in the memory, the second is the way in which the recollection of a memory epitome can evoke an emotional response.

One of the primeval sources discussing the fine art, the Ad Herennium emphasizes the importance of using emotionally hit imagery to ensure that the images will be retained in memory:

We ought, so, to set up images of a kind that can adhere longest in retention. And we shall practice and so if we institute similitudes as striking every bit possible; if nosotros set up images that are not many or vague but agile; if we assign to them infrequent beauty or singular ugliness; if we ornamentation some of them, as with crowns or imperial cloaks, and so that the similitude may be more distinct to us; or if we somehow disfigure them, as past introducing one stained with blood or soiled with mud and smeared with ruddy paint, so that its form is more striking, or by assigning certain comic effects to our images, for that, too, volition ensure our remembering them more than readily.[27]

On the other paw, the image associated with an emotion will telephone call up the emotion when recollected. Carruthers discusses this in the context of the way in which the trained medieval retentivity was idea to be intimately related with the evolution of prudence or moral judgement.

Since each phantasm is a combination not only of the neutral form of the perception, but of our response to it (intentio) apropos whether it is helpful or hurtful, the phantasm by its very nature evokes emotion. This is how the phantasm and the memory which stores it helps to crusade or bring into being moral excellence and ethical judgement.[28]

In modernistic terminology, the concept that contains salient, bizarre, shocking, or only unusual information will be more than easily remembered. This can be referred to as the Von Restorff upshot.

Repetition [edit]

The well-known function of repetition in the common process of memorization of course plays a role in the more complex techniques of the fine art of memory. The earliest of the references to the art of retention, the Dialexis, mentioned to a higher place, makes this clear: "repeat once more what you hear; for past ofttimes hearing and saying the same things, what y'all accept learned comes complete into your retentiveness."[29] Similar communication is a commonplace in subsequently works on the art of retentivity.

Techniques [edit]

The art of memory employed a number of techniques which can be grouped as follows for purposes of word, however they were commonly used in some combination:

Architectural mnemonic [edit]

The architectural mnemonic was a central group of techniques employed in the art of retentiveness. It is based on the use of places (Latin loci), which were memorized by practitioners as the framework or ordering structure that would 'contain' the images or signs 'placed' within it to record experience or cognition. To employ this method one might walk through a building several times, viewing distinct places within it, in the same order each time. After the necessary repetitions of this process, one should be able to retrieve and visualize each of the places reliably and in order. If one wished to remember, for case, a spoken language, 1 could suspension up the content of the speech communication into images or signs used to memorize its parts, which would and then be 'placed' in the locations previously memorized. The components of the spoken language could then exist recalled in order by imagining that one is walking through the edifice again, visiting each of the loci in guild, viewing the images there, and thereby recalling the elements of the speech in order. A reference to these techniques survives to this day in the common English phrases "in the first identify", "in the second identify", so forth.[30] These techniques, or variants, are sometimes referred to every bit "the method of loci", which is discussed in a split section below.

The primary source for the architectural mnemonic is the bearding Rhetorica ad Herennium, a Latin work on rhetoric from the beginning century BCE. Information technology is unlikely that the technique originated with the author of the Ad Herennium. The technique is also mentioned by Cicero and Quintilian. According to the account in the Ad Herennium (Book III) backgrounds or 'places' are similar wax tablets, and the images that are 'placed' on or within them are like writing. Real concrete locations were apparently commonly used as the footing of retentiveness places, as the author of the Ad Herennium suggests

it will be more advantageous to obtain backgrounds in a deserted than in a populous region, because the crowding and passing to and fro of people confuse and weaken the impress of the images, while solitude keeps their outlines sharp.[31]

However, real physical locations were not the only source of places. The writer goes on to propose

if we are not content with our ready-made supply of backgrounds, we may in our imagination create a region for ourselves and obtain a about serviceable distribution of appropriate backgrounds.[32]

Places or backgrounds hence require, and reciprocally impose, order (often deriving from the spatial characteristics of the physical location memorized, in cases where an actual physical structure provided the ground for the 'places'). This order itself organizes the images, preventing confusion during recall. The bearding author too advises that places should exist well lit, with orderly intervals, and singled-out from one another. He recommends a virtual 'viewing distance' sufficient to allow the viewer to encompass the infinite and the images it contains with a single glance.

Turning to images, the anonymous author asserts that they are of two kinds: those establishing a likeness based upon subject, and those establishing a likeness based upon a word. This was the ground for the subsequent distinction, commonly found in works on the art of memory, between 'memory for words' and 'memory for things'. He provides the following famous instance of a likeness based upon subject:

Often we encompass the tape of an entire affair by 1 note, a single image. For example, the prosecutor has said that the defendant killed a human being by toxicant, has charged that the motive for the crime was an inheritance, and alleged that at that place are many witnesses and accessories to this deed. If in order to facilitate our defense nosotros wish to remember this first point, we shall in our first background course an image of the whole affair. Nosotros shall picture the human being in question as lying ill in bed, if nosotros know his person. If we do not know him, nosotros shall nonetheless accept some one to be our invalid, but not a man of the lowest class, and then that he may come up to listen at once. And we shall place the defendant at the bedside, holding in his right hand a loving cup, and in his left hand tablets, and on the fourth finger a ram's testicles (Latin testiculi suggests testes or witnesses). In this way nosotros tin record the man who was poisoned, the inheritance, and the witnesses.[33]

In order to memorize likenesses based on words he provides an example of a poesy and describes how images may be placed, each of which corresponds to words in the verse. He notes however that the technique will not piece of work without combination with rote memorization of the poesy, so that the images call to mind the previously memorized words.

The architectural mnemonic was also related to the broader concept of learning and thinking. Aristotle considered the technique in relation to topica, or conceptual areas or issues. In his Topics he suggested

For just equally in a person with a trained retentiveness, a retentivity of things themselves is immediately acquired by the mere mention of their places, so these habits too will make a man readier in reasoning, because he has his premisses classified before his mind's eye, each under its number.[34]

Graphical mnemonic [edit]

The architectural mnemonic is ofttimes characterized equally the fine art of memory itself. Withal primary sources testify that from very early on in the development of the art, non-physical or abstract locations and/or spatial graphics were employed as retention 'places'. Peradventure the almost famous example of such an abstract system of 'places' is the memory system of Metrodorus of Scepsis, who was said by Quintilian to have organized his retentivity using a system of backgrounds in which he "found three hundred and sixty places in the twelve signs of the zodiac through which the dominicus moves". Some researchers (50.A. Mail service and Yates) believe it likely that Metorodorus organized his memory using places based in some way upon the signs of the zodiac.[35] In any case Quintilian makes it clear that non-alphabetic signs can be employed every bit memory images, and even goes on to mention how 'autograph' signs (notae) can be used to signify things that would otherwise exist impossible to capture in the class of a definite prototype (he gives "conjunctions" as an case).[36]

This makes it articulate that though the architectural mnemonic with its buildings, niches and iii-dimensional images was a major theme of the fine art as practiced in classical times, it often employed signs or notae and sometimes even not-physical imagined spaces. During the period of migration of barbarian tribes and the transformation of the Roman empire the architectural mnemonic fell into decay. Notwithstanding the use of tables, charts and signs appears to have continued and developed independently. Mary Carruthers has made it clear that a trained memory occupied a central place in late antique and medieval pedagogy, and has documented some of the ways in which the development of medieval memorial arts was intimately intertwined with the emergence of the volume as nosotros understand it today. Examples of the evolution of the potential inherent in the graphical mnemonic include the lists and combinatory wheels of the Majorcan Ramon Llull. The Art of Signs (Latin Ars Notoria) is also very likely a development of the graphical mnemonic. Yates mentions Apollonius of Tyana and his reputation for memory, equally well as the clan between trained memory, astrology and divination.[37] She goes on to suggest

Information technology may take been out of this atmosphere that there was formed a tradition which, going hush-hush for centuries and suffering transformations in the process, appeared in the Middle Ages equally the Ars Notoria, a magical art of memory attributed to Apollonius or sometimes to Solomon. The practitioner of the Ars Notoria gazed at figures or diagrams curiously marked and called 'notae' whilst reciting magical prayers. He hoped to gain in this way knowledge, or retentivity, of all the arts and sciences, a different 'nota' being provided for each subject field. The Ars Notoria is perhaps a descendant of the classical art of memory, or of that hard branch of it which used the shorthand notae. It was regarded as a especially blackness kind of magic and was severely condemned by Thomas Aquinas.[38]

Textual mnemonic [edit]

Carruthers'due south studies of retention suggest that the images and pictures employed in the medieval arts of memory were not representational in the sense we today empathize that term. Rather, images were understood to role "textually", as a type of 'writing', and non as something different from information technology in kind.[39]

If such an assessment is right, it suggests that the apply of text to recollect memories was, for medieval practitioners, merely a variant of techniques employing notae, images and other not-textual devices. Carruthers quotes Pope Gregory I, in support of the idea that 'reading' pictures was considered to be a variation of reading itself.

It is i thing to worship a picture, information technology is another by means of pictures to learn thoroughly the story that should exist venerated. For what writing makes present to those reading, the same picturing makes present to the uneducated, to those perceiving visually, because in information technology the ignorant come across what they ought to follow, in information technology they read who exercise not know messages. Wherefore, and particularly for the mutual people, picturing is the equivalent of reading.[39]

Her work makes clear that for medieval readers the act of reading itself had an oral phase in which the text was read aloud or sub-vocalized (silent reading was a less common variant, and appears to have been the exception rather than the dominion), then meditated upon and 'digested' hence making it one's own. She asserts that both 'textual' activities (picturing and reading) take as their goal the internalization of knowledge and experience in retentiveness.

The apply of manuscript illuminations to reinforce the memory of a particular textual passage, the use of visual alphabets such as those in which birds or tools represent letters, the employ of illuminated upper-case letter letters at the openings of passages, and fifty-fifty the structure of the mod book (itself deriving from scholastic developments) with its index, table of contents and chapters reflect the fact that reading was a memorial practice, and the use of text was simply another technique in the arsenal of practitioners of the arts of memory.

Method of loci [edit]

The 'method of loci' (plural of Latin locus for identify or location) is a general designation for mnemonic techniques that rely upon memorized spatial relationships to institute, order and recollect memorial content. The term is most ofttimes found in specialized works on psychology, neurobiology and retentiveness, though it was used in the aforementioned general fashion at to the lowest degree equally early as the first one-half of the nineteenth century in works on Rhetoric, Logic and Philosophy.[40]

O'Keefe and Nadel refer to "'the method of loci', an imaginal technique known to the aboriginal Greeks and Romans and described by Yates (1966) in her book The Art of Retentivity also as by Luria (1969). In this technique the field of study memorizes the layout of some building, or the arrangement of shops on a street, or a video game,[41] [42] or whatsoever geographical entity which is composed of a number of discrete loci.[43] When desiring to remember a ready of items the subject 'walks' through these loci and commits an detail to each one by forming an image between the item and any distinguishing feature of that locus. Retrieval of items is achieved by 'walking' through the loci, allowing the latter to activate the desired items. The efficacy of this technique has been well established (Ross and Lawrence 1968, Crovitz 1969, 1971, Briggs, Hawkins and Crovitz 1970, Lea 1975), as is the minimal interference seen with its use."[44]

The designation is not used with strict consistency. In some cases it refers broadly to what is otherwise known as the art of memory, the origins of which are related, according to tradition, in the story of Simonides of Ceos: and the collapsing banquet hall discussed above.[45] For instance, afterwards relating the story of how Simonides relied on remembered seating arrangements to call to mind the faces of recently deceased guests, Steven M. Kosslyn remarks "[t]his insight led to the development of a technique the Greeks chosen the method of loci, which is a systematic manner of improving one's memory by using imagery."[46] Skoyles and Sagan signal that "an ancient technique of memorization called Method of Loci, by which memories are referenced directly onto spatial maps" originated with the story of Simonides.[47] Referring to mnemonic methods, Verlee Williams mentions, "One such strategy is the 'loci' method, which was developed by Simonides, a Greek poet of the fifth and sixth centuries BC"[48] Loftus cites the foundation story of Simonides (more or less taken from Frances Yates) and describes some of the well-nigh basic aspects of the use of infinite in the art of memory. She states, "This particular mnemonic technique has come to be called the "method of loci".[49] While place or position certainly figured prominently in aboriginal mnemonic techniques, no designation equivalent to "method of loci" was used exclusively to refer to mnemonic schemes relying upon space for arrangement.[fifty]

In other cases the designation is by and large consistent, just more specific: "The Method of Loci is a Mnemonic Device involving the creation of a Visual Map of one's house."[51]

This term can be misleading: the ancient principles and techniques of the art of retentiveness, hastily glossed in some of the works merely cited, depended equally upon images and places. The designator "method of loci" does not convey the equal weight placed on both elements. Training in the art or arts of memory as a whole, equally attested in classical artifact, was far more inclusive and comprehensive in the treatment of this discipline.[52]

See also [edit]

- Anamonic

- Haraguchi's mnemonic system

- Interference theory

- Linkword

- Mnemosyne in Greek mythologie a Titanness and 'female parent' of the nine Muses; as well the river of retentivity in the Hades

- Mnemonist

- Mnemonic link system, major system, peg system, dominic system, and goroawase system

- Retentivity sport

- Piphilology

- Series position effect

- Spacing effect

- The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two

- Zeigarnik upshot

Practitioners & exponents [edit]

Institutional:

- Lodge Mother Kilwinning[53]

Individual:

- St. Thomas Aquinas

- Giulio Camillo

- Thomas Bradwardine

- Giordano Bruno

- Robert Fludd

- Giovanni Fontana

- William Fowler

- Hugh of St. Victor

- Johannes Romberch

- William Schaw

- World Memory Championships participants, an annual mental sports event since 1990.

Notes [edit]

- ^ In her general introduction to the subject area (The Art of Memory, 1966, p4) Frances Yates suggests that "it may be misleading to dismiss it with the label 'mnemotechnics'" and "The give-and-take 'mnemotechnics' inappreciably conveys what the bogus memory of Cicero may take been like". Furthermore, "mnemotechnics", etymologically speaking, emphasizes practical application, whereas the art of retentiveness certainly includes general principles and a certain caste of 'theory'.

- ^ a b Carruthers 1990, p. 123

- ^ Simonedes of Ceos, the poet credited by the ancients with the discovery of fundamental principles of this fine art, was agile effectually 500 BCE, and in any case a fragment known every bit the Dialexis, which is dated to about 400 BCE contains a short department on memory which outlines features known to exist cardinal to the fully developed classical art. Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, 1966, pp 27-xxx. The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Tertiary Edition, Ed. Hornblower and Spawforth, 1999, p1409.

- ^ Yates, 1966, pp. 29

- ^ Yates, 1966, pp. 27-30

- ^ Aristotle's assertion that we cannot contemplate or understand without an paradigm in the mind'southward eye representing the thing considered was as well highly influential. Aristotle, De Anima three.8 in The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984)

- ^ Yates, 1966, pp. 1-2

- ^ Cicero, De oratore, Ii, lxxxvi, 351-4, English translation past East.W. Sutton and H. Rackham from Loeb Classics Edition

- ^ Carruthers 1990, 1998

- ^ "artificial retentivity - definition of artificial retentiveness in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English . Retrieved 2016-11-24 .

- ^ Carruthers & Ziolkowski 2002

- ^ Bolzoni 2004

- ^ Spence 1984

- ^ Bruno's apply of groups of words may also be associated with the use of shorthand, or with techniques associated with shorthand in antiquity. Yates (1966) mentions the possibility of a relationship between shorthand notae and the art(south) of memory (p15 footnote 16) and the possible role of shorthand notae in 'magical' memory training (p43). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd Edition, 1999, in the article "tachygraphy") discusses the formal characteristics of late Hellenistic shorthand manuals, noting "These prove a fully organized system, composed of a syllabary and a (and then-called) Commentary, consisting of groups of words, arranged in fours or occasionally eights, with a sign attached to each, which had to memorized." This tin can be compared with Bruno's atria in De Imaginum, Signorum, et Idearum Compositione (1591) in which groups of 24 words are each associated within an atrium with Atrii Imago (e.k. Altare, Basili, Carcer, Domus, etc.)

- ^ Frances Yates, The Fine art of Retention, 1966; Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, 1964

- ^ e.g. the "Memory Theater" of Giulio Camillo discussed past Yates (1966, pp 129-159)

- ^ Yates 1966

- ^ Frances Yates, The Art of Retentiveness, 1966, Ch. 12

- ^ Carruthers & Ziolkowski 2002; Rossi 2000

- ^ Culianu 1987

- ^ Rossi 2000 p102; Bolzoni 2001

- ^ Carruthers 1990, pp. 94-95

- ^ Carruthers 1990, p. seven

- ^ Carruthers 1990, pp. 81-82

- ^ Carruthers 1990, p. 82

- ^ De memoria et reminiscentia, 452 viii-16, cited in Yates, The Fine art of Memory, 1966, p34

- ^ Ad Herrenium, III, xxii

- ^ Carruthers, 1990, pp. 67-71

- ^ from the excerpt of this piece of work bachelor in Yates, The Art of Retention, 1966, p29

- ^ Finger, Stanley. (1994). Origins of neuroscience : a history of explorations into brain function. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-nineteen-506503-four. OCLC 27151391.

- ^ Book III, xix, 31, Loeb Classics English translation by Harry Caplan

- ^ Book Three, xix, 32, Loeb Classics English translation by Harry Caplan

- ^ Book Three, xix, 33, Loeb Classics English translation by Harry Caplan

- ^ Aristotle, Topica, 163, 24-30 (translated by Due west.A. Pickard-Cambridge in Works of Aristotle, ed. W.D. Ross, Oxford, 1928, Vol. I), cited in Yates, The Art of Memory, 1966, p. 31

- ^ Yates, 1966, pp. 39-42

- ^ Quintilian, Institutio oratoria, Xi, two, 23-26, Loeb Edition English language translation by H. E. Butler

- ^ Yates 1966, pp. 42-43

- ^ Yates 1966, p. 43

- ^ a b Carruthers 1990, p. 222

- ^ e.g. in a discussion of "topical memory" (yet some other designator) Jamieson mentions that "memorial lines, or verses, are more than useful than the method of loci." Alexander Jamieson, A Grammar of Logic and Intellectual Philosophy, A. H. Maltby, 1835, p112

- ^ Legge, Eric L. G.; Madan, Christopher R.; Ng, Enoch T.; Caplan, Jeremy B. (2012). "Building a memory palace in minutes: Equivalent memory functioning using virtual versus conventional environments with the Method of Loci". Acta Psychologica. 141 (3): 380–390. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.09.002. PMID 23098905 – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ "Artificial Memory Palaces - Retention Techniques Wiki". artofmemory.com.

- ^ "Retentivity Palace - Memory Techniques Wiki". artofmemory.com.

- ^ John O'Keefe & Lynn Nadel, The Hippocampus every bit a Cognitive Map, Oxford Academy Press, 1978, p389-390

- ^ Frances Yates, The Art of Retentiveness, University of Chicago, 1966, p1-2

- ^ Steven K. Kosslyn, "Imagery in Learning" in: Michael Due south. Gazzaniga (Ed.), Perspectives in Retentivity Enquiry, MIT Press, 1988, p245; Kosslyn fails to cite any case of the use of an equivalent term in menses Greek or Latin sources.

- ^ John Robert Skoyles, Dorion Sagan, Up From Dragons: The Evolution of Homo Intelligence, McGraw-Colina, 2002, p150

- ^ Linda Verlee Williams, Teaching For The Two-Sided Mind: A Guide to Right Brain/Left Encephalon Teaching, Simon & Schuster, 1986, p110

- ^ Elizabeth F. Loftus, Man Memory: The Processing of Information, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1976, p65

- ^ For example, Aristotle referred to topoi (places) in which memorial content could be aggregated - hence our modernistic term "topics", while another main classical source, Rhetorica ad Herennium (Bk Three) discusses rules for places and images. In general Classical and Medieval sources depict these techniques as the art or arts of memory (ars memorativa or artes memorativae), rather than as whatsoever putative "method of loci". Nor is the imprecise designation current in specialized historical studies, for example Mary Carruthers uses the term "architectural mnemonic" to draw what is otherwise designated "method of loci".

- ^ Sharon A. Gutman, Quick Reference Neuroscience For Rehabilitation Professionals, SLACK Incorporated, 2001, p216

- ^ "Rhetorica advertisement Herennium Passages on Memory". www.laits.utexas.edu.

- ^ 2d Schaw Statutes Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, 1599

References [edit]

- Bolzoni, Lina (2001). The Gallery of Retention . University of Toronto Printing. ISBN0-8020-4330-v.

- Bolzoni, Lina (2004). The Web of Images. Ashgate Publishers. ISBN0-7546-0551-five.

- Carruthers, Mary (1990). The Book of Retentiveness (outset ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-38282-3. (limited preview on Google Books)

- Carruthers, Mary (1998). The Craft of Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-58232-half-dozen.

- Carruthers, Mary; Ziolkowski, Jan (2002). The Medieval Arts and crafts of Memory: An album of texts and pictures. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN0-8122-3676-nine.

- Culianu, Ioan (1987). Eros and Magic In The Renaissance. University of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-12316-ii.

- Dudai, Yadin (2002). Memory from A to Z . Oxford Academy Press. ISBN0-19-850267-2.

- Foer, Joshua (1996). Moonwalking with Einstein: The Fine art and Scientific discipline of Remembering Everything. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN978-ane-59420-229-2.

- Rossi, Paolo (1657). Logic and the Art of Memory. University of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-72826-9.

- Small-scale, Jocelyn P. (1956). Wax Tablets of the Mind. London: Routledge. ISBN0-415-14983-5.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1978). The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci . New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN0-14-008098-eight.

- Yates, Frances A. (1966). The Art of Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN071265545X.

External links [edit]

- TED talk: Joshua Foer on feats of retentiveness anyone can do

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_memory

Postar um comentário for "The True Art of Memory Is the Art of Attention Form of Expression"